Inman’s Inventory Insanity series on the current supply shortage.

PART 1: Why are there no homes for sale in America?

PART 2: Notes from ‘exhausted’ agents on the front lines of a crazy market

PART 3: The secret economic forces fueling the housing shortage

PART 4: What it’s like being a homebuyer when there are no homes to buy

PART 5: When will this supply shortage end?

Part 1: Why are there no homes for sale in America?

Inventory has been tight for a long time now, but this spring agents across the country are seeing something different — and more difficult

Brian Evans thought his clients were going in with a strong offer.

Evans, a Redfin agent in the Washington, D.C., area, told Inman he was recently working with buyers who wanted a home that was listed for $850,000. Homes in the area have in the past sold for around 10 percent over their asking prices, so when his clients offered $150,000 over it seemed like they’d be strong contenders.

They weren’t.

Instead, the home ultimately generated 14 offers and sold for a whopping $230,000 over its asking price. What had seemed like a strong offer had in the end only put Evans’ clients “in the middle of the pack.” They weren’t even close to winning.

“When you’re blown out by $80,000, it’s crushing,” Evans said of his clients. “But there’s nothing you can do. You feel flattened.”

A year into the coronavirus pandemic, “flattened” appears to be the operative word. Finally, infections and deaths are down, the curve is flattening and there’s hope that life and the economy are inching back to normal. But in real estate, a persistent lack of inventory that has been a long-running problem is now colliding with the spring buying market, amplifying a housing shortage to heights many agents have never before seen in their careers.

Case in point: “Inventory is as low as I’ve seen it for a spring market in the six years I’ve been practicing as a real estate agent,” Evans said. “This spring has really just blown things out of the water.”

Where exactly this inventory shortage is going is anybody’s guess, but according to economists and agents across the country, it’s apparent that the problem is extremely widespread. And that means a multitude of consumers and industry pros are having their expectations flattened day after day by bidding wars, endless price increases, and a deluge of offers on the few homes that do hit the market.

How bad is the problem?

Data provided to Inman from several different companies offers a staggering view into the current housing shortage.

For example, Redfin found in late March that 39 percent of homes during the prior four weeks sold above their listing prices. That was an all-time high, and was 15 percentage points higher than what was happening during the same period one year earlier.

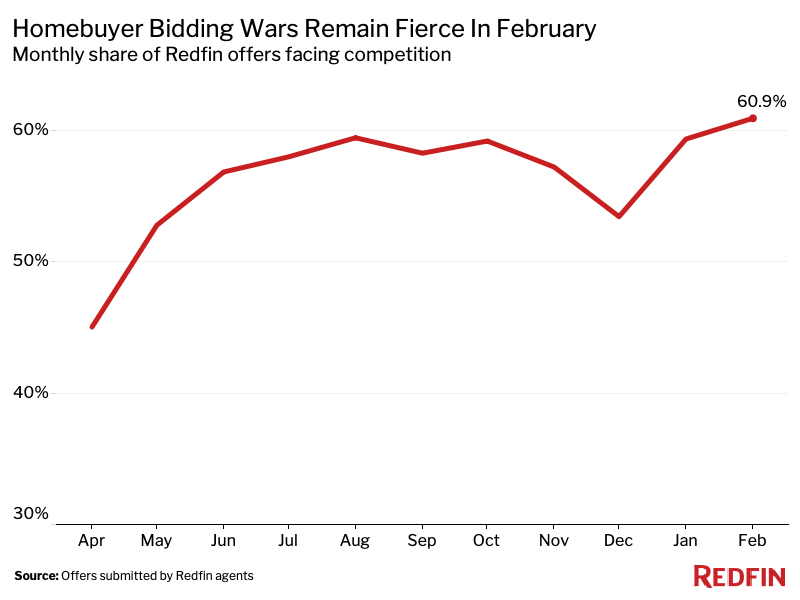

The company further found that more than 60 percent of the offers that its own agents wrote in February faced bidding wars. This was high even compared to prior months during the coronavirus pandemic, when supply and demand have persistently been out of balance.

“Battles between buyers are more intense than ever,” the company concluded in a write-up of the findings.

Redfin also found in late March that the pandemic has changed a host of buyer behaviors. Among other things, more buyers are now making larger down payments and waiving contingencies. Buyers are touring more homes. And the percent who are paying over a home’s asking price has jumped from 21.2 percent before the pandemic to 34.4 percent now.

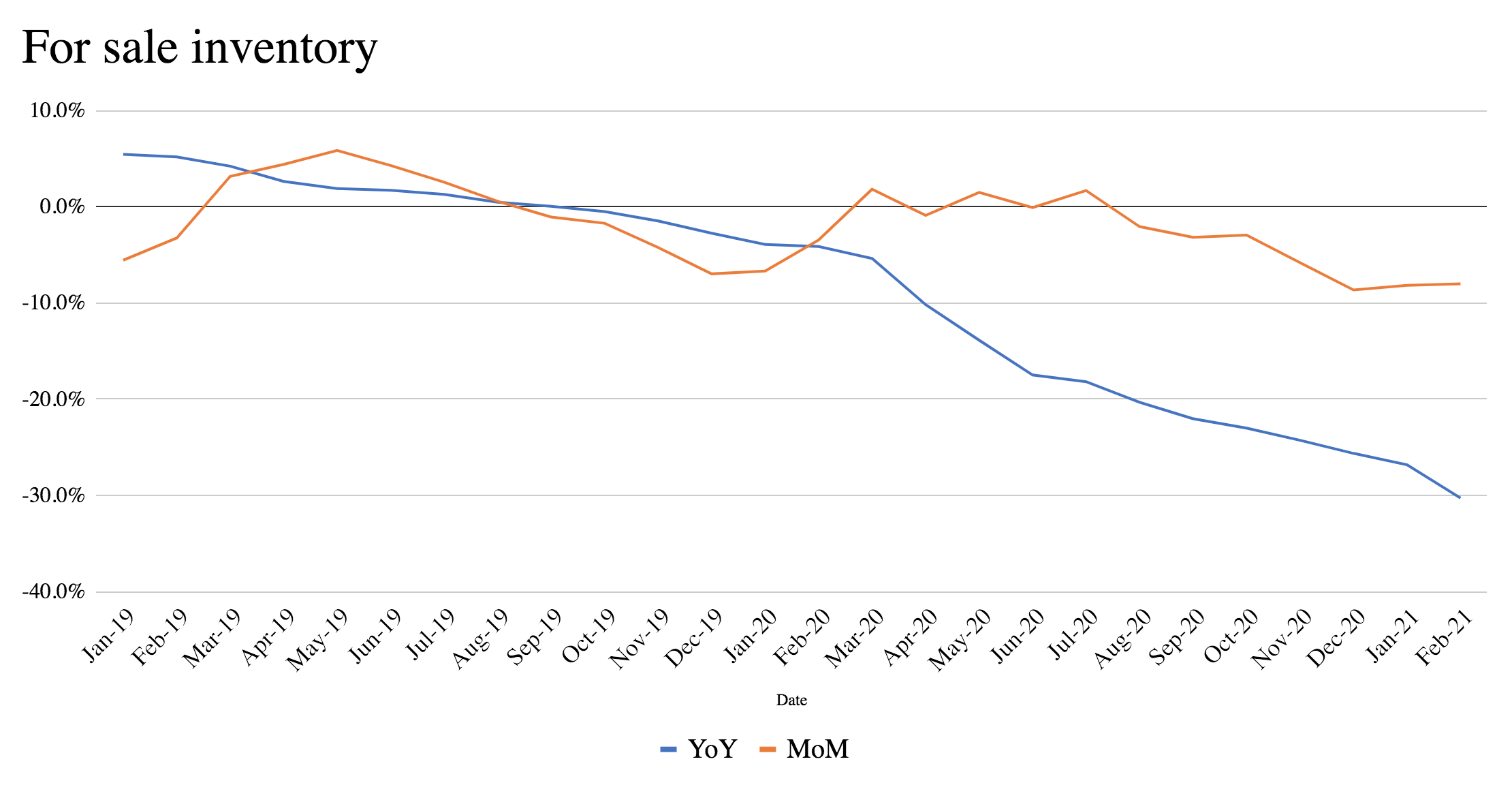

Data from Zillow further shows steep declines in the number of for-sale listings over the last year. Especially noteworthy in this data is the fact that these steep declines are new; as recently as spring of 2019, the number of listings was actually up compared to prior months and years.

Year-over-year declines in f0r-sale listings are represented in blue, while month-over-month declines are represented in orange. Credit: Jim Dalrymple II via Zillow data

The Zillow data ultimately shows that by February of 2021, the number of homes for sale in the U.S. was down more than 30 percent compared to one year prior. For comparison, the number of homes for sale in February of 2020 was only down 4.1 percent compared to the same period in 2019. So, things are vastly tighter this year than they were last year.

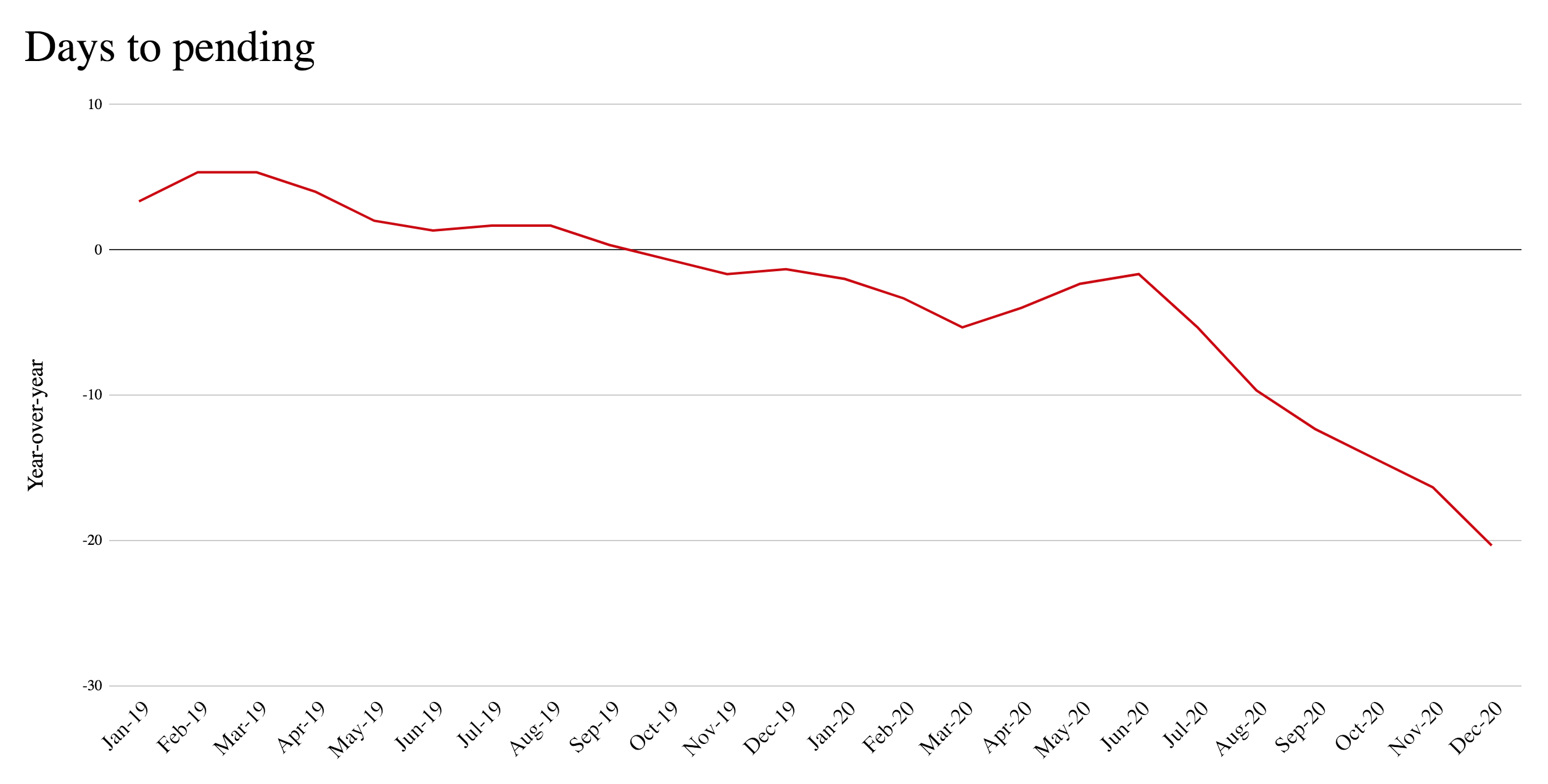

Zillow’s data similarly shows that the days it takes for a home to go under contract (“days to pending” in the graph below) has steadily declined — including precipitously since last summer. And that decline became even steeper in the fall, meaning competition has only become more fierce.

Credit: Jim Dalrymple II via Zillow data

Zillow’s data shows inventory declines happened in almost every major U.S. metro area, though some are faring worse than others. At the top of the list is Raleigh, North Carolina, which saw for-sale listings fall more than 50 percent year-over-year in February.

A number of other cities saw reductions of near or above 40 percent: New Orleans; Riverside, California; Salt Lake City, Utah; Cleveland, Ohio; Providence, Rhode Island; and Jacksonville, Florida. Even Detroit saw a 36.8 percent year-over-year decline in inventory in February.

It’s difficult to generalize about the cities that are most impacted. Salt Lake and Raleigh, for example, are younger and tech-oriented. Providence likely benefits from its proximity to other major metro areas. Meanwhile Cleveland and Detroit lie in the Rust Belt and haven’t made many headlines for their hot real estate markets in recent years.

The only thing that’s really clear from all these many data points, then, is that the current inventory shortage is widespread. The whole country, in other words, has seemingly turned into San Francisco.

(Ironically, San Jose, the largest city in California’s Bay Area, is the only place in Zillow’s data set that saw year-over-year increases in inventory in February. That’s surely due to the continued ability of tech workers to operate remotely from their companies.)

Of course conditions vary by location, but the takeaway from all this is that the inventory shortage is severe, it is widespread and it is something different than what was going on pre-pandemic, when home prices also had been rising. As the curves on those graphs indicate, the supply shortage has been getting much worse just in the last few months.

Why is the problem so bad?

There are several big trends that have produced this inventory shortage. And the first long predates the pandemic.

The building shortfall

Jeff Tucker, a senior economist for Zillow, told Inman that the roots of this current inventory shortage date back more than a decade, when housing construction mostly stopped in the wake of the housing bubble collapse.

“Ever since 2007, we were radically under-building,” Tucker explained, “especially single-family homes.”

Some of the reasons for that under-building are probably self-apparent: As the housing and lending markets collapsed, builders had a harder time financing projects and there was less demand for the product they were making.

But over time, other challenges emerged as well. Tucker explained that the construction industry depends in some areas on migrant and immigrant workers. However, as the sector dried up many of those workers returned to their home countries and never came back. Other workers also found jobs in different industries, such as energy. The result was a labor shortage that has continued to hamstring the construction industry right up until the present day.

“The housing crash was just so much worse for the homebuilding industry than any other industry,” Tucker said. “And a lot of that capacity for building homes went away. This is a lasting scar for this industry.”

The rising home prices of the last few years have incentivized builders to catch up, and Tucker said they are making some progress. But the supply of homes has been falling behind for so long now that catching up could take some time.

“They’re building very fast,” Tucker explained. “But I think it will take several years to meet this excess demand.”

Agents on the ground have witnessed the impact of this trend firsthand. Tim Heyl — a team leader in Austin with Keller Williams and the founder of real estate startup Homeward — got started in the real estate industry in 2009, at the height of the housing-induced Great Recession. There were plenty of homes on the market at the time, but that also meant “builders were not building for years.”

“We need something like 1 million home starts a year across the country,” he said.

The demographic shift

To make matters worse, this period of underproduction has also coincided with unprecedented demand.

Danielle Hale, chief economist at realtor.com, agreed that there has been a decade of under-building in the construction industry, and pointed to that problem as among the main drivers of soaring home costs. On top of that, Hale also explained millennials are the largest generation since the baby boomers and have been gradually hitting homebuying age in recent years. That trend is peaking right now.

“The largest chunk of the millennial generation is hitting 30,” Hale explained. “I think that’s one of the things that has really created this tipping point. You kind of have this perfect storm of factors coming together to really make the housing market unlike what we’ve seen in recent years.”

These are complex trends, but the takeaway here is that the current housing shortage has been brewing for a long time. That drove wild price growth for years in expensive markets like San Francisco and Los Angeles, but in recent months it has also spilled out into just about everywhere.

The coronavirus pandemic

The building shortfall and demographic shift have both been brewing for a long time, but of course there’s something else going on right now as well: COVID-19.

Tucker described the pandemic as “a short-term component stacked on this long-term trend” of under-building. It’s a trend that has been observed throughout the pandemic, but Tucker said essentially what happened was after a brief pause in housing demand a year ago, interest in owner-occupied homes came “roaring back.”

Part of that had to do with people suddenly wanting more space in their homes, or wanting to escape pricey cities for more affordable regions. Extremely low interest rates also helped fuel demand.

And Tucker pointed to what economists have described as a “K-shaped” recovery, which is when different parts of the economy improve at different rates following a recession. In the case of the last year, Tucker noted that the pandemic has left some consumers uniquely well-positioned to buy real estate.

“A lot of office workers in the upper third of the income distribution were doing fine and had more disposable income than in a normal year,” he said, “and also had a need for space.”

Many such consumers have helped drive up housing costs, in part because fewer existing homeowners have been listing their houses.

“Usually the way market economies work is, if you don’t have enough of something, the price goes up and that incentivizes people to produce more,” Hale said. “In this case, it should incentivize homeowners to sell their home.”

Curiously, though, that hasn’t happened to the same extent that it did in the past. Hale said the issue may be that consumers fear they won’t be able to find new housing if they sell their existing homes. Other factors may include concerns about health and safety amid COVID-19 outbreaks, or simply that many people are satisfied with their current situation.

“It could just be that a lot of homeowners are happy where they are and they don’t need to move,” Hale said.

Either way, though, the pandemic has been a unique period for housing, during which time long-running supply issues collided with a rare and sometimes-baffling resistance among consumers to list their homes. The result has been escalating prices, bidding wars and a situation that few in the industry saw coming.

“I would say that this is definitely the first time we’ve seen properties sell as quickly as they have in our data history,” Hale concluded. “It’s pretty historic.”

Part 2: Notes from ‘exhausted’ agents on the front lines of a crazy market

‘There is no middle class any more,’ one industry leader said of working in real estate this year. ‘You’re either crushing it or you’re struggling’

Though the real estate market has long been competitive in pockets of the U.S., the great thing about America is that there’s typically always been somewhere else that’s affordable. Drive an hour or two outside of San Francisco or New York, and you could find a deal. It’s an idea that’s baked into the country’s foundational mythology.

Now, however, that idea is collapsing in entirely new ways. Thanks to a unique convergence of underproduction of homes, demographic shifts, and the coronavirus pandemic, home price explosion isn’t just limited to the coasts anymore. Instead, there are bidding wars across Minnesota and Connecticut and Florida and pretty much everywhere in between.

To get a sense of what is going on, Inman reached out to dozens of real estate agents. The takeaway from these conversations is that they’re exhausted after writing dozens of offers and doing endless showings. Their clients are disheartened after losing countless bidding wars. Agents are an entrepreneurial bunch and many remain upbeat — and in some cases are doing well financially — but the workload is unquestionably heavier now.

Here are some of their stories:

Jill Stencil, Legacy Premier Realty, Cape Coral, Florida

Stencil recently had a listing that got nine offers within 24 hours of it going live. She’s seen homes in her market go for as “little” as $30,000 over their asking prices, and for as much as $100,000. And she’s had to write offer after offer for clients, even when she knows they’ll keep getting beaten.

“I have to call them up and say, ‘Hey we lost another one. We did the best we could,’” Stencil told Inman. “You’re riding that wave with them. That’s hard.”

Stencil said that in her area “cash is king” and buyers who need financing don’t stand much of a chance. The situation has become so competitive that she recently advised some FHA clients to simply bow out and wait for a better time. Those clients understood, but generally speaking Stencil said it’s just extraordinarily tough right now to be a buyer in her region.

“People are crying,” she added of her buyers who have lost over and over.

The situation has also trickled into other markets. Apartment complexes in her area are filling up with would-be buyers who can’t find homes. In other cases, people have begun buying mobile homes as they wait for a better opportunity. And asked how the real estate community in her area is holding up, Stencil replied that everyone is “exhausted.”

“We are running around like crazy people,” she added.

Tiara Smith, Keller Williams, Columbia, Maryland

Smith is currently working with four buyers. One of them just had an offer accepted — but not before looking for two months and having six or seven previous rejections. In the end, getting a winning offer required looking in a different county, waiving contingencies, offering more earnest money and “looking at everything we could do” to seem more competitive.

“He couldn’t believe it had finally gone through,” Smith said of her client when he found out the offer had been accepted.

Smith is typically a buyer’s agent, and explained that this year that means working with clients for much longer because it’s so difficult for them to actually get a home.

“They want to go on these showings every day, day in and day out,” Smith explained. “It’s our duty to do our best, but I also have a family. I can’t do showings 24/7. We’re having a hard time, too. We’re human.”

Tim Heyl, Keller Williams Realty International, Austin, Texas

When Heyl first started in real estate back in 2009, there was somewhere in the neighborhood of 19,000 homes for sale in Austin, Texas. This spring, he said it’s closer to 1,000.

“We’re just way way behind on inventory,” he said, adding that prices are up by 30 percent in his area.

But the price increases haven’t deterred buyers.

Instead, Heyl has seen listings getting as many as 150 offers. And he recalled one house that fetched $400,000 over its asking price. In total, he said that Austin has only nine days of inventory, when a healthy market should have six months. The impact of this situation is that buyers are gradually hardened by the experience of losing multiple times.

“If it’s your first time to make your offer, you’re almost definitely going to lose,” Heyl explained. “You’re competing against people who have already been losing a bunch. You’re competing against all these people who are coming from a place of pain.”

Rebecca Nemeth, Zip Code East Bay, Oakland, California

Nemeth works on the east side of San Francisco Bay, which has historically been a relatively more affordable part of the expensive region. But she said that lately conditions have gone “nuts” as wealthy buyers flood into the area from San Francisco.

“We’ve always had more demand than supply,” she explained. “What’s changed is that we have some buyers who have inordinate amounts of money. But we also still have normal humans who want to live here.”

Many of those well-heeled buyers are millennials who work in technology and make hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. Others have substantial backing from family, thanks in part to baby boomer parents whose own houses have appreciated over the years.

Either way though, homes in the area are routinely selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars over their asking prices, and one even nabbed $1 million more.

“At first we were kind of in shock,” she said.

Shannon Todd, Cromer and Company, Anderson, South Carolina

Anderson lies about halfway between Atlanta and Charlotte, North Carolina, and Todd told Inman that historically asking prices in the city of just under 30,000 people were a “starting point” that typically went down during negotiations. But in recent months, that has flipped and houses are now uniformly selling for more than their asking price.

“It’s just changed so much,” she said. “It’s really, really frustrating. Summertime last year wasn’t like this.”

One reason it’s frustrating is because buyers in the area have expectations that are now out of alignment with the market, Todd explained. They talk to friends and family who bought houses before this spring price spike, and can’t grasp how they now have to offer as much as $25,000 over a home’s asking price to be competitive.

Todd described recently writing up a 10th offer for one of her clients. In some cases, she continued, clients have also submitted offers, then seen online that the house is pending (to another buyer, of course) before they ever heard back from the listing agent.

“I love my buyers,” she added. “But nobody is going to give them a chance right now. I hate it.”

Yu Jie Chen, RE/MAX Results, Eden Prairie, Minnesota

Chen has been in real estate for 12 years, but in all that time she hasn’t seen anything like what’s been happening in her market since about February.

She told Inman offers in her area are typically coming in between $15,000 and $30,000 over a home’s asking price. To be competitive, buyers also have to waive inspections, have fast closing times and turn over huge sums of earnest money. If someone comes in with an offer at a home’s asking price, it now sounds like they’re trying to lowball the sellers. It wasn’t always this way.

“It’s like a rollercoaster,” she said. “It’s really tough. It is a very different market. And it’s exhausting working with buyers.”

Chen wasn’t sure when conditions might calm down, though she speculated that the current inventory shortfall in her region could linger until the fall or beyond. And on top of all the other challenges, the real estate industry itself is getting more and more crowded.

“It’s difficult because right now we have the most agents,” she said, “and the least inventory.”

Dan Smith, Anvil Real Estate, Orange County, California

Smith, a principal at Anvil, and his wife, a broker at his company, began the process of looking for a second home in Orange County, California, several months ago. They wanted a space that they could provide for the agents at their company to use, and they began making offers with waived contingencies, short closing times and 50 percent down payments.

“We didn’t even get counters,” Smith told Inman.

The couple shifted strategies multiple times in an effort to find a property, but in the end they only managed to win by finding a place that needed work and which Smith said perhaps wasn’t being shown in the most effective ways. Overall, the experience was difficult, and unprecedented.

“These conditions are common today,” Smith explained, “but not really in the history of real estate.”

Asked about the agents in his community, Smith said the overall sentiment among many is one of discouragement.

“As long as I’ve been in real estate, which is now 24 years, I’ve never seen such a dramatic noticeable case of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots,’” Smith said. “There is no middle class any more. You’re either crushing it or you’re struggling.”

Kerrian Latty, Equity Realty Group, Trumbull, Connecticut

As 2021 was beginning, Latty decided she was going to commit to helping first-time buyers. But little did she know how much of a commitment that would be.

“Half the battle is educating our clients on how to bid now and telling them they have to block out the norm of trying to get a good deal,” Latty told Inman. “After you do that half, then you’re just trying to get your offer in. You’re praying that the listing agent is truly presenting all these offers.”

Latty’s market is adjacent to New York City, so some buyers are coming in with lots of cash and high salaries. She described working with several such buyers, who love that they can get yards and driveways at a relative bargain.

But that also makes it difficult for locals. Latty said historically in her market buyers typically offered at or below a home’s asking price, and rarely had to compete with more than one or two other offers. Now, however, buyers are having to offer $25,000 or $50,000 over asking, and may be competing with 20 offers. The difference is stark.

“This market is the craziest market I’ve ever seen,” she said.

For buyers relying on financing, especially FHA financing, it typically takes losing several bidding wars before they’re even able to grasp how competitive it really is. And of course, that means more showings, more writing offers and more exhaustion for agents.

“It takes being rejected for them to understand that they can’t get a deal,” Latty said. “This year for buyer’s agents is terrible.”

Part 3: The secret economic forces fueling the housing shortage

Many consumers may not realize it, but they’re increasingly competing against institutional investors and contending with soaring building costs

Agents are exhausted and consumers are stretched thin. But despite everyone being fed up, the ongoing housing supply shortage drags on with no end in sight.

As Inman has previously reported, the problem is multifaceted. The coronavirus pandemic, for example, has reshuffled job markets. And at the same time, a years-long building shortfall and a wave of millennials hitting homebuying age have further exacerbated the problem.

But those aren’t the only issues. In fact, there are multiple other forces that have, perhaps inadvertently, conspired to make housing both more scarce and more expensive — but which are also largely off the radar of most consumers. Despite their lower profile, though, these forces are having a tremendous impact on the housing market right now.

For our purposes here, we’ll focus on two such forces: the soaring cost of building materials, and the spiking interest in housing among investors. Together, these two things are major contributors to today’s housing market, and the lack of inventory that is sweeping so many markets.

Building supplies are getting way more expensive

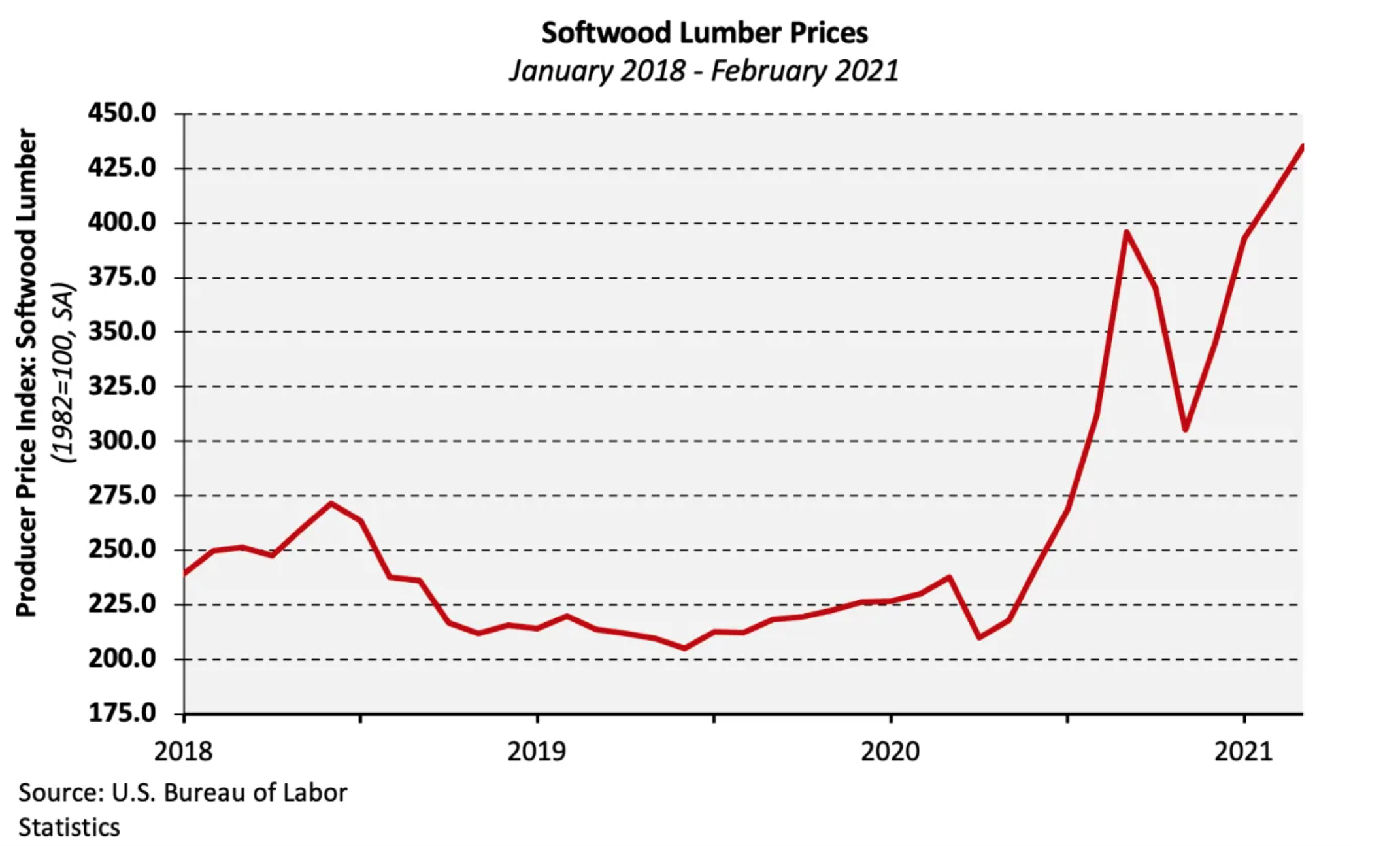

The cost of building supplies has been ticking upward for a long time now, but according to David Logan — a senior economist with the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) — the pandemic made the problem worse. That’s because the companies that make things like lumber bet that there would be a “precipitous drop in housing demand” during the pandemic, and that bet proved to be wrong.

“Producers of lumber, they shut down like most every other business needed to,” Logan told Inman. “But when production came back, mills had curtailed their production by as much as 50 percent.”

Logan called this a “fatal mistake” on the part of lumber companies, in part because demand for housing itself has surged and in part because on top of that DIY home remodeling has also become more popular during the pandemic.

The result is a kind of triple whammy where supply is low, while demand from both contractors and everyday consumers is higher than ever. It’s no surprise then that, according to Logan, the cost of lumber has tripled since a year ago.

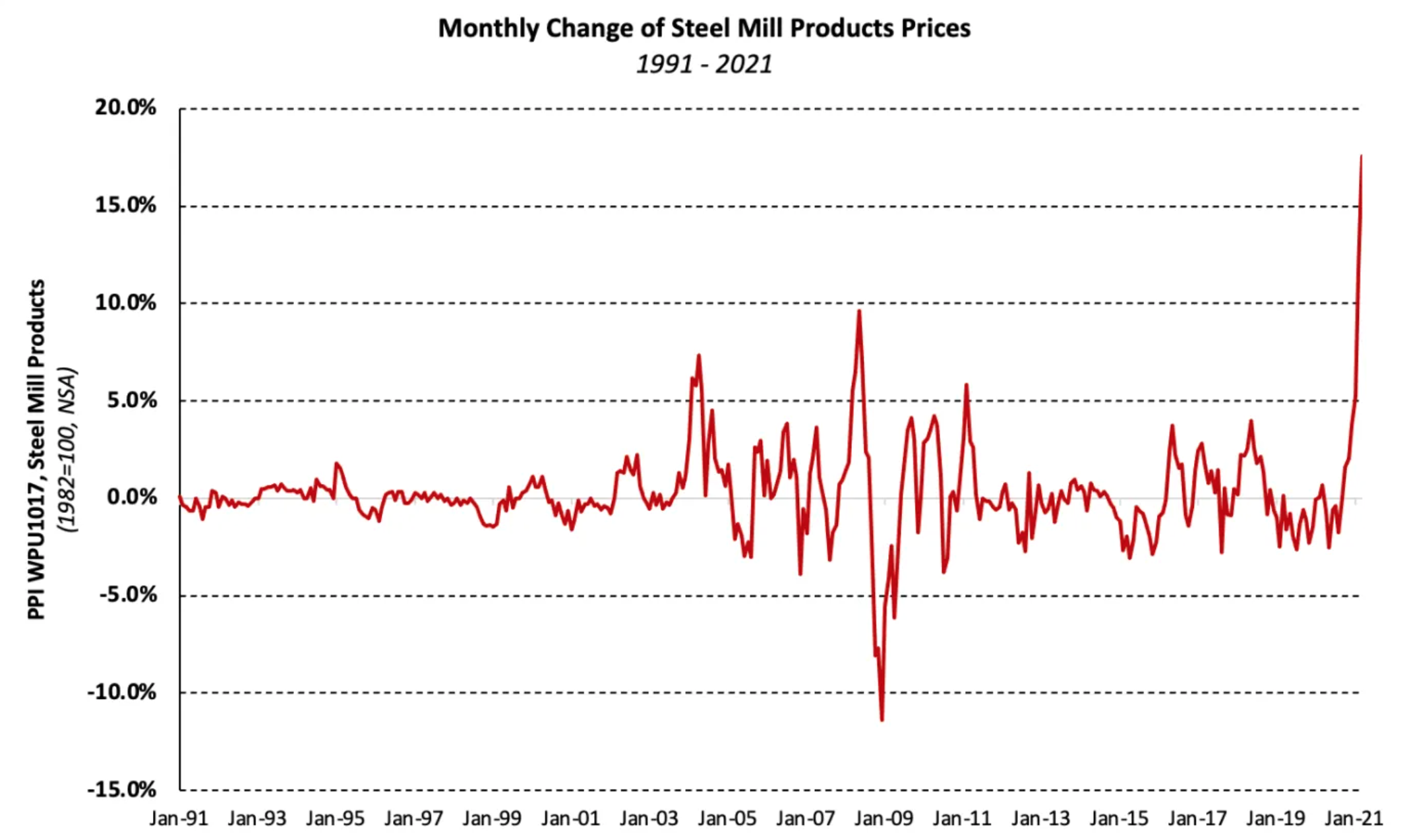

Credit: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via NAHB

“I would say it’s certainly unprecedented in so far as a surge of demand unexpectedly coincides with a large decline in supply,” Logan added.

Higher material prices are now translating into higher costs to build homes, and that in turn translates to higher sales prices for consumers. Just by February, the NAHB estimated that this trend had added more than $24,000 to the cost of a newly built single-family home.

Data from the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics further bears this out, showing that the prices for plywood, lumber, veneer, pallets and various other items have jumped up recently.

Lumber may be the most prominent material impacted by this trend, but Logan also said it is “by no means the only culprit in this increase of the cost to built a home.” Other materials that have seen price increases include concrete, the oriented strand board (OSB) that is used in home wall paneling, and many other products.

“We’re seeing shortages in everything from some steel products to paint to toilets and appliances,” Logan said. “It’s not that builders and homebuyers aren’t going to get them, it’s that it can literally take months.”

Another NAHB report further notes that the price of steel mill products has jumped 22 percent in just the last three months.

Credit: NAHB

The consequences of these price increases are far-reaching. In a series of reports, NAHB has revealed that contractors this spring are now having difficult conversations with their clients about the cost of materials and that those costs are delaying critical home repairs. The costs are also cutting into the supply of affordable homes, especially in lower-cost suburbs where wood-frame building is the most common construction method.

Logan doesn’t expect these conditions to last forever, but in the meantime he said the prevailing sentiment among builders is one of “concern.”

Institutional investors are flocking to the housing industry

At the same time that building homes is getting more expensive, deep-pocketed investors are also snapping up more and more housing. Rick Palacios Jr., director of research for John Burns Real Estate Consulting, told Inman that right now investors are buying 20 percent of all homes in the U.S. Asked if that was enough to sway prices and housing supply, Palacios answered without hesitation: “yes.”

“That percentage gets even higher in a lot of markets,” he added. “Almost a quarter of all housing transactions are going to investors.”

Palacios pointed to Phoenix as an example, saying that nearly 30 percent of sales in the Arizona city are to investors. Las Vegas, Houston, and Tampa, Florida, also all have higher-than-average numbers of sales going to investors. Many of these markets also happen to be iBuying hotspots, and Palacios said firms such as Opendoor can end up having a major impact on the supply landscape in cities where they are active.

Of course, “investors” is a broad category. Palacios explained that it includes everyone from fix-and-flip operators to iBuyers to rental companies. But the result of all this interest among investors is that would-be homeowners are facing more competition and higher prices.

A report from John Burns Real Estate Consulting — which was provided to Inman — further teases this idea out, showing that investors have zeroed in on lower-cost homes. The report also notes that “cash purchases account for 67 percent of homes sold below $100k and 31 percent of homes sold between $100k and $200k.”

Some of this investor activity makes obvious sense. Given that there is a supply shortfall, as well as soaring prices, flippers stand to make a significant profit by simply buying houses and then selling them a short time later. Palacios said places like Phoenix and Boise, Idaho, are ideal backdrops for that kind of activity.

Interest from landlords, on the other hand, may be slightly less understandable given that right now they have to pay top dollar for their properties. That contrasts significantly from the housing bubble in 2008, when institutional investors were able to snap up thousands of houses at a relative bargain.

However, Palacios said that “there’s a global quest for yield” going on among investors right now. At the same time, yields from vehicles like U.S. Treasuries have tanked while investment in commercial real estate became unappealing thanks to COVID-related shutdowns of stores, restaurants and hospitality businesses.

Residential real estate, and especially single-family housing, looks relatively safe by comparison. And Palacios said recent years have ultimately offered a kind of proof-of-concept that shows this type of investment works. As a result, institutions like pension and sovereign wealth funds — which may have mandates to invest in U.S. real estate — have increasingly gravitated toward housing. And if they have to pay top dollar for the properties, so be it because they’re in it for the long haul.

“Today’s investors are investing for both quick appreciation as well as yield and safety compared to other alternative investments,” Palacios added.

The John Burns report further notes that investors have gravitated toward residential real estate as a hedge against inflation and in an effort to diversify their assets.

This trend may not be readily apparent to consumers or their agents. When someone loses a bidding war, after all, they may never find out exactly who won. But like rising material costs, it is happening in the background and having a big impact. And that impact is likely to stick around for the foreseeable future.

“Housing investors are going wild, again,” the report ultimately concludes. “Limited new and resale housing supply, low mortgage rates, a global reach for yield, and what we’re calling the institutionalization of real estate investors are setting the stage for a home price boom that could stretch on for years, similar to the early 2000s.”

Part 4: What it’s like being a homebuyer when there are no homes to buy

‘It’s always still a punch in the gut,’ one would-be homebuyer recently said after losing one house after another to higher offers

Lauren Wasteney knew buying a house would be tough. She just didn’t know it’d be this tough.

Wasteney is one of the millions of Americans who have decided to buy a home recently, and who subsequently crashed headfirst into a market with historically low inventory. The situation has left agents across the country exhausted and overworked as they spend months taking clients to showings that translate into failed offers. And it has worried economists, who see problems with housing affordability getting worse and worse.

But at the most fundamental level, the inventory shortage is a problem first for consumers. They’re the ones putting up more and more money for houses whose appreciation seems unstoppable.

And when they lose one bidding war after another, they’re the ones who can’t get into the housing they need. Stories of struggling consumers abound, but below are two that highlight what it’s like to be a middle-class buyer in a market that seems to no longer have room for everyone.

Buying in the Bay Area

Wasteney began searching for a home in February, though she had been, in her own words, “haunting Zillow” for long before that. Her budget topped out in the high $400,000 range, and she explained that while she would have liked to save for a few more years, she ultimately decided to move forward because interest rates are so low.

Wasteney’s search focused on the eastern side of California’s Bay Area, where cities like Oakland and Alameda have traditionally been somewhat more affordable than San Francisco itself.

Wasteney told Inman the first home she zeroed in on was listed for around $460,000. She knew she would have to offer more than the property’s asking price, and $475,000 seemed reasonable to her.

But that price was a nonstarter: Before Westerly could even submit an offer, her agent called and revealed the seller had already received offers for more than $500,000. Westerly ultimately gave up on the property and never sent her offer in.

“It was more of a derailed sort of offer,” she said.

Undeterred, though, Wasteney moved on to another property she said was “really slapdash” and an obvious flip. The home was asking $430,000 and Wasteney decided to offer $450,000 — although she did so reluctantly.

“I really didn’t think it was worth $450,000,” she said.

But someone else apparently did, because Wasteney once again lost the bid and never even heard what the final price was.

Finally, she found a third property. This one was a condo in Richmond, at the northern tip of the San Francisco Bay. It was listed for $450,000 and seemed promising because most lenders wouldn’t finance a loan on the property — meaning the competition should have been less fierce. On top of that, the condo was located a short distance from Wasteney’s work, making it even more attractive to her.

She ultimately offered $480,000. She spent a week agonizing without hearing back. And then, she lost again.

“I didn’t necessarily expect to be accepted,” she said, “but it’s always still a punch in the gut. You do start imagining yourself in it.”

These numbers may not sound wild to battle-hardened observers of the Bay Area housing scene, where some listings have recently sold for as much as $1 million over their asking prices. But they do highlight how not everyone in the region is a tech millionaire, and how people with otherwise middle-class lifestyles are being squeezed out entirely.

As of this writing, for example, Richmond — where Wasteney was looking and which has a population over 100,000 — had just 33 properties listed for sale on Zillow (and some are lots, rather than houses). Every house in the city is listed for less than $500,000, meaning it should be exactly the kind of place someone like Wasteney could afford.

However, a review of homes that sold over the last month shows that five homes in Richmond went for over $1 million, and 25 home sold between $700,000 and $1 million. Only 15 homes sold for less than $500,000 during that time period, the majority of them well over their asking prices.

In one case, a home that sold for $420,000 in October appears to have sold again two weeks ago for $650,000. That means a buyer like Wasteney has been priced out of one of the last affordable enclaves in the region in just five months.

Wasteney still didn’t have a house when she talked to Inman, and her voice was tinged with the same sense of exhaustion that many agents seemed to have when they too spoke with Inman.

Most recently she has been considering a home that’s subject to a probate sale. But Wasteney said it’s obvious the home needs work, though there’s no inspection report right now so it’s not clear how deep the property’s issues run. She said it “would be pretty risky” to put an offer on the house, but in the Bay Area high risk has become par for the course.

“I think my experience is pretty common, there’s always someone who is offering more,” Wasteney concluded. “Basically it sucks. It really sucks.”

Buying in Austin

The Bay Area isn’t the only place that’s brutal for buyers right now. Case in point: One Texas woman, who asked to speak anonymously, said that she’s spent the last several months trying to buy a condo in Austin. The would-be homebuyer had a friend who sold a property in a condo complex 18 months ago for just under $390,000, so she began her home search in that same complex.

Very quickly, however, the woman had a rude awakening: A unit comparable to her friend’s was now listed for $499,000.

“I was just kind of going, ‘oh my gosh, wow,’” she said.

The price jump was too hard a pill to swallow, so the woman didn’t make an offer.

By January, she had found another property in Austin listed for $599,000. After consulting with her agent, the woman offered $630,000 but days later found out she was “on the low end” among the offers the seller received.

“I was mystified, confused,” she said, “because the listing price doesn’t have any meaning. It’s arbitrary.”

She also discovered she had offered the lowest amount of earnest money, and that her financing contingency had made her less competitive.

By March, she was looking once again at the same condo complex where her friend had owned. But now, a comparable unit was listed for more than $600,000. Moreover, the owners wanted to stay in the home after the sale, rent free, for at least 60 days.

The woman was out of town when the condo hit the market, and sellers in Austin have come to expect responses almost immediately. So she made an offer sight-unseen while traveling in a different state. But it was half-hearted effort that only upped the offer price by about $10,000, and which ultimately proved fruitless.

“I didn’t know how I’d feel paying over $600,000 for something I could have bought a year and a half ago for $389,000,” she concluded, adding that she still hasn’t found a place in the city and maybe never will. “I’m to the point where I’m about to give up on Austin.”

Instead, she has focused her efforts on Houston, where she currently lives. In Houston, she lost her first bidding war after offering $75,000 over the asking price on a single family home. She had also offered to cover closing costs, and told the buyer she’d match other offers.

“I don’t know what the actual price ended up being,” she said, “but probably at least $100,000 over asking. I bawled after I didn’t get it.”

This story, at least, has something close to a happy ending: The woman is currently closing on a house in Houston.

The home is located in a gated community where one of the woman’s friends lives. She found the property by having the friend chat up the guard at the gate, who happened to have the inside scoop on couple in the community that was planning to sell. The friend then knocked on the couple’s door, and ultimately connected the prospective buyers and sellers.

It was the kind of rigmarole that would have sounded like overkill years ago, but which increasingly is the way buyers have to approach the market.

“You just have to get creative,” the woman said. “You do whatever you have to.”

Part 5: When will this supply shortage end?

There’s something really strange happening right now: There are seemingly no homes for sale, and yet the number of actual sales this year is probably going to be up compared to 2020.

How could that be? If there’s a housing shortage, shouldn’t that mean fewer homes will sell?

These questions get at the heart of the current inventory shortage. And more importantly, they hint at how it might, eventually, resolve.

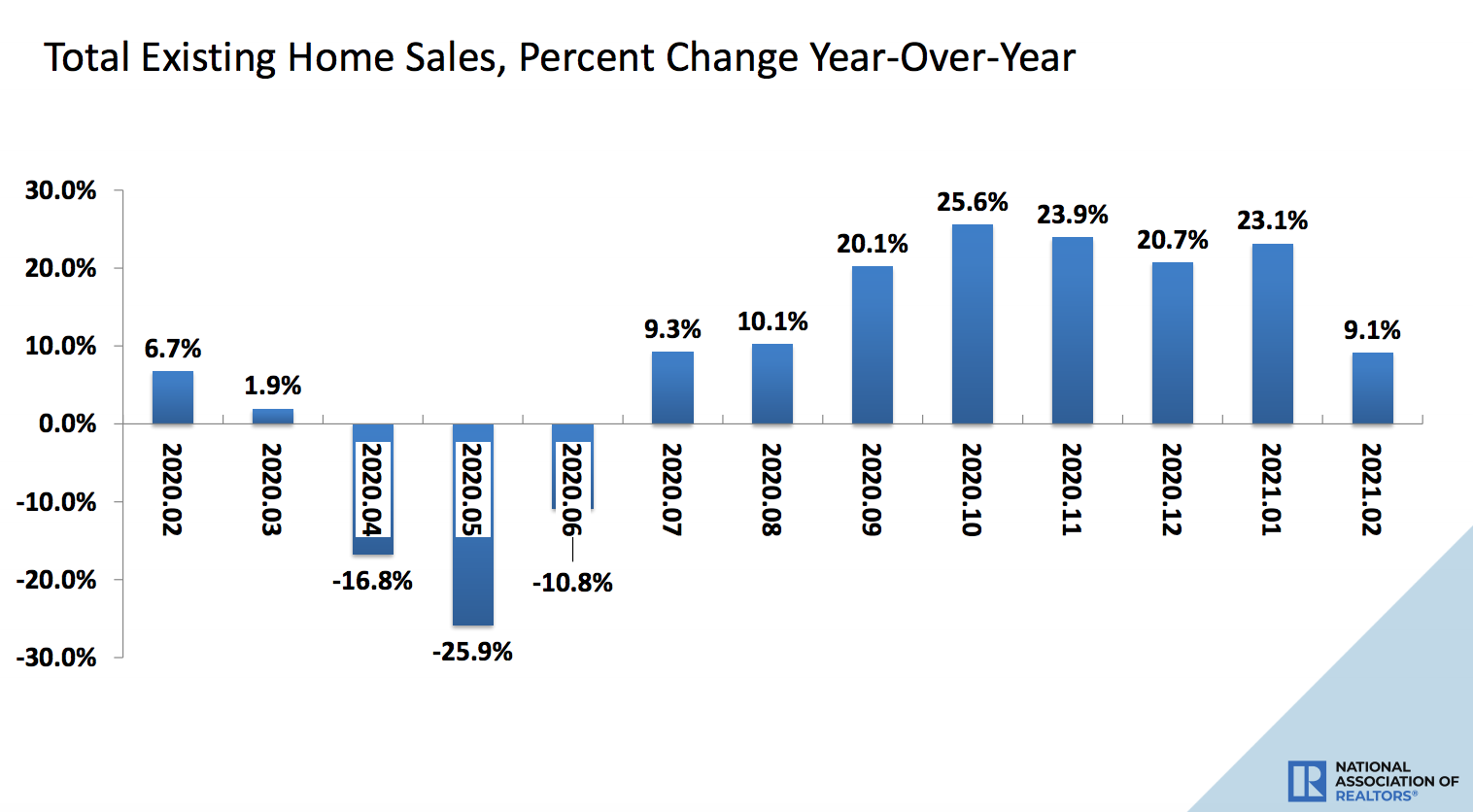

As Inman has reported this week, agents are exhausted, consumers are literally crying after losing bidding wars, and economists are calling the situation unprecedented. On the other hand, data that the National Association of Realtors provided to Inman projects a total of nearly 6.5 million existing home sales in 2021. That’s up significantly from just 5.64 sales in 2020 and 5.34 in 2019.

What these numbers highlight is the fact that “inventory” is a measure of the balance between supply and demand. For example, if the number of homes on the market suddenly doubled, there’d be more supply. But if the number of hopeful buyers quadrupled at the same rate, all those new listings still wouldn’t be enough. There’d be an inventory shortage. And that’s basically what’s going on right now: Demand is outpacing supply.

NAR data shows that despite the shortage, the number of homes sold each month has been up year-over-year for most of the pandemic. Credit: NAR

Why does this matter?

Put simply, it’s because it shows that there are two ways out of this mess: Either supply has to go up to meet high demand, or that demand has to go down. In reality, the solution will probably be some combination of the two, but unfortunately either way the current shortage isn’t likely to dissipate in the immediate future.

Increasing supply

Building more houses

The most obvious way to address an inventory shortage is to simply increase supply. This is the solution that would probably make everyone — agents, consumers, lenders, etc. — most happy because it would mean everyone gets the house they need.

“The only way we can really fix this is we’ve got to build more,” Matthew Gardner, chief economist for Windermere Real Estate, told Inman.

But there are real obstacles to making that happen.

Gardner explained that in some places, such as California or his own home base in the Pacific Northwest, land near job centers is increasingly scarce. That makes development more expensive, and in turn translates to high home prices for consumers — hardly the solution to an affordability crisis.

On top of that, labor costs have skyrocketed. This is partly because, as Inman previously reported, the construction labor pool never fully recovered after the Great Recession. But Gardner also pointed to a deeper issue that could pose challenges: “Labor costs are massive because no one is going to vocational school to become a carpenter or an electrician or a plumber.”

Danielle Hale, chief economist for realtor.com, made a similar point when talking to Inman about the challenges of increasing the supply of new homes. And the challenges in the building sector means new construction tends to focus on a narrow slice of the market.

“Trade workers were increasingly hard to come by at the cost builders were willing to pay,” she explained. “So, builders did an okay job of building at the higher price point. But we weren’t seeing the same thing at other price points.”

Hale further noted that many local governments lately have been “kind of making it difficult to get permitting through” for condos, meaning urban infill is also more difficult to do right now.

And of course the cost of construction materials is way up. This is in part because of pandemic-induced reductions in what manufacturers can make, but there are other factors at play as well. For example, Gardner said the Trump-era tariffs on Canadian lumber are still in place.

Still, even with all of these challenges, it is profitable to build houses right now and Jeff Tucker, a senior economist for Zillow, told Inman that contractors “are catching up.”

But everyone who spoke with Inman for this series said the U.S. has been building too little housing for so long that new construction alone isn’t going to fix the current problem in a reasonable timeframe.

“They’re building very fast,” Tucker said. “But I think it will take several years to meet this excess demand.”

Enticing more sellers to enter the market

The other way to increase supply is to convince more sellers to list their homes. There are many theories as to why this hasn’t happened yet: fears about the pandemic, fears about not finding a new place, wanting to capitalize on future price gains, and even simply contentedness among consumers with their current situation.

Whatever the causes, though, the economists who spoke with Inman said they do expect more sellers to list in the coming months. Tucker pointed to the rollout of vaccines, as well as continued rising prices, and said both things could “bring some sellers off the sidelines.”

He also pointed to what he described as a “silver tsunami” as aging baby boomers leave homeownership.

“That will clearly start to shift the inventory dynamics,” he said.

Still, aside from changes associated with the end of the pandemic, many of these shifts are very long term, and they’ll be happening against a backdrop of more and more millennials hitting homebuyer age.

All of which is to say the supply shortages currently plaguing the U.S. housing market probably won’t be “solved” literally for years.

“I would say, if you’re looking around for a cohort that won’t have quite the same amount of growing pains,” Tucker concluded, “You could look at Gen Z. We could expect them to have a little less fierce competition.”

Reducing demand

Declining interest from pandemic buyers

As has been widely covered, the coronavirus pandemic drove interest from buyers who wanted more space and who wanted to move from pricey places to cheaper ones. For higher income workers, it also in some cases resulted in more time and more money to spend on housing.

But that may be changing.

Dan Smith, a principal at Anvil Real Estate in Orange County, California, told Inman that as the pandemic has improved, would-be real estate consumers in his area have begun to spend less time on home searches.

“We’re already noticing our market here in Orange County beginning to slow slightly,” Smith explained. “We’re noticing more people going on vacation, and they don’t have time to look at houses.”

In other cases, Smith continued, buyers are simply getting a breather from the craziness of the pandemic, and have realized they may not need a new house, or at least may not need it quite as urgently. These changes are slight — multiple offers and bidding wars are still common in Smith’s area — but they do seem to hint at a shift on the horizon.

“Maybe not with prices yet,” Smith said, “but we’ve noticed it impact the market slightly.”

This is an anecdotal example, but it’s certainly possible that the homebuying frenzy the pandemic inspired could lessen as vaccines tamp down the outbreak.

Mortgage rates

Rising mortgage rates may also prove to be a critical factor in reducing demand. And they may have a much more rapid impact than things like building more houses.

According to NAR’s projections, average 30-year fixed interest rates should hit 3 percent in the second quarter of 2021, and then ultimately rise to 3.3 percent by the second quarter of 2022. These are still great rates, but they are higher than the average of 2.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, and that will translate into higher monthly payments for consumers.

Tucker doesn’t think rates alone will be enough to fundamentally change conditions, but they do seem to be having at least some impact already.

“It’s starting to cool off buyer interest,” he said.

Hale made a similar argument, saying that the soaring prices of the past year can’t last forever.

“Mortgage rates have enabled prices to rise so much without hitting consumers in the pocketbook,” she explained. “But now we’re starting to see mortgage rates turn around and consumers just won’t be able to have the same spending power that they had before.”

Affordability

Whatever happens with interest rates, though, prices can’t rise forever.

“Ultimately there must always be a relationship between incomes and home prices,” Gardner said, adding that affordability has become a serious challenge in the housing market already. “It’s what keeps me up at night.”

So far, apparently, the market hasn’t hit its affordability breaking point. People are still paying more and more for homes. But eventually that growth will have to level out.

“At a certain point you will see affordability become a bigger factor,” Hale said.

The timeline for improvement

All of this is to say that there’s good news and less-than-good news. The good news is that smaller shifts on all of these fronts — construction, new listings, rates, etc. — should mean that the current extremes won’t last forever.

“I don’t think we’ll see a decade of quickly escalating home prices,” Hale said.

Gardner expects prices to continue rising for some time, but thinks appreciation may slow in 2022 or 2023 — a timeline that many agents also mentioned when speaking with Inman for this series.

But the less-than-good news is that there’s no silver bullet and inventory shortages are likely to stick around in some form or another for the foreseeable future.

“We haven’t seen the peak,” Gardner concluded. “This year is going to be a very frustrating year for homebuyers.”